![]()

A Method in His Madness: The Role of Japonisme and Cloisinisme, Colour, and Nature in Vincent van Gogh's Irises

By Adam Stead ©

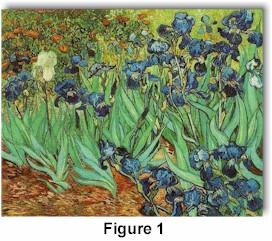

Perhaps more than any other artist in history, Vincent van Gogh embodies the notion of the tormented genius sacrificing his mental health for his art. Consequently, separating the artist's work from his affliction is near impossible, but in the last half-century his art has been reassessed to show that Van Gogh's madness is not the only aspect of his work. Indeed, although much of Van Gogh's oeuvre is highly emotive, certain aspects of the artist's later work remain true to a certain stylistic formula consisting of elements derived from Japonisme and Cloisinisme; Van Gogh's use of complementary colours based on various influences; and his view of the spiritual power inherent in nature. These elements were continually employed by Van Gogh during the last four years of his life, and are readily visible in his vibrant and luxurious oil painting of the Irises, (1889) (fig.1). This essay seeks to explore the place of the Irises in Van Gogh's oeuvre, and the

relationship of the work to Van Gogh's view of nature; the stylistic elements that compose the Irises, and the relationship of these formal elements to Van Gogh's view of nature; and lastly, the role of Japanese art, Cloisinisme, and colour in Van Gogh's working method, and how these techniques appear in the Irises and how they relate to the notion of Van Gogh's art being fully generated out of his madness.

Perhaps more than any other artist in history, Vincent van Gogh embodies the notion of the tormented genius sacrificing his mental health for his art. Consequently, separating the artist's work from his affliction is near impossible, but in the last half-century his art has been reassessed to show that Van Gogh's madness is not the only aspect of his work. Indeed, although much of Van Gogh's oeuvre is highly emotive, certain aspects of the artist's later work remain true to a certain stylistic formula consisting of elements derived from Japonisme and Cloisinisme; Van Gogh's use of complementary colours based on various influences; and his view of the spiritual power inherent in nature. These elements were continually employed by Van Gogh during the last four years of his life, and are readily visible in his vibrant and luxurious oil painting of the Irises, (1889) (fig.1). This essay seeks to explore the place of the Irises in Van Gogh's oeuvre, and the

relationship of the work to Van Gogh's view of nature; the stylistic elements that compose the Irises, and the relationship of these formal elements to Van Gogh's view of nature; and lastly, the role of Japanese art, Cloisinisme, and colour in Van Gogh's working method, and how these techniques appear in the Irises and how they relate to the notion of Van Gogh's art being fully generated out of his madness.

The breadth of Van Gogh's artistic production is impressive, especially when one considers that he was artistically active for only ten years (1880-90). During this relatively short period, however, Van Gogh passed through many different artistic styles: The dark, earthy paintings of peasant life in his native Netherlands (1880-85); the gradual lightening of his palette and his adoption of impressionist techniques in Paris (1886-87); the radiant and sun-drenched paintings of his Arles period (1888-89); and the energetic and powerful paintings executed during the last fifteen months of his life, which he spent in Saint-Rémy and Auvers-sur-Oise (1889-90).

It was in the last phase of Van Gogh's life, in Saint-Rémy, that the Irises was painted. This period in his artistic production is marked by tempestuous lines, sharp, vibrant colours, and heavy, dark outlines. A proliferation of subjects taken from nature also emerged during this time: Cypress trees, tossing wheat fields, and silvery olive trees. It was also during his stay at the asylum at Saint Paul-de-Mausole in Saint-Rémy that Van Gogh became cognizant of the permanence of his illness, an illness that was then deemed to be a form of epilepsy (Overbeek 14-17). Van Gogh responded to this terrifying prospect by painting during the intermittent periods of sanity—painting that which consoled him: nature. Indeed, nature in Saint-Rémy was of the utmost importance for Van Gogh because it provided him with consolation, and, as Ingo Walther suggests, Van Gogh saw an intense spiritual power in nature, a power that consumed him like that of his fervent religious devotion ten years earlier. It was nature that Van Gogh turned to during his periods of tranquillity (Walther 65). In this way, Van Gogh's art during this period is empirical: a constant examination of nature for its underlying meaning. As the artist himself stated: "I can't help adding that one can never study nature too much and too hard" (Letters 2: 429). Theo, Vincent's brother, was aware of Vincent's ability to paint nature powerfully. Of the Irises he suggested: "...It is one of your good things. It seems to me that you are stronger when you paint true things like that..." (Letters 3: 554).

One does not need to search for the subject matter in the Irises: the sprawling floral growth is presented directly and purely. Curvilinear forms proliferate the work. Writhing and tormented lines in the leaves contrast with the serene, sculpted lines of the petals. Indeed, few straight lines exist in this entanglement of organic growth. The absence of straight lines and the profusion of organic forms undermines any attempts at a traditional rendering of one-point perspective. Space is, however, suggested by the overlapping of the leaves, as well as by the darker foreground outlines compared to the less distinct circumscriptal elements in the background forms. The intense blue of the foreground petals, in contrast to the lighter green field behind, force the foreground elements towards the viewer which also suggests space (Schapiro 19). The central formal element in this work, however, is the use of complementary colours. The Prussian blue and violet petals in the lower right corner contrast with the orange marigolds in the upper left hand corner, creating a strong horizontal tension from the upper left corner to the lower right corner. Similarly, the intense red soil in the left foreground contrasts with the light green in the upper right corner, creating another horizontal tension in the work. This tension, however, is balanced by the cool analogous colours of the blue, green, and violet forms. The texture in the work borders on the real: the thick, agitated, and impastoed brushstrokes in the soil add a dimension of tactility to the work, which invests the painting with a tangible embodiment of nature. This agitation, however, is balanced by the velvet-like appearance of the petals. The undulating motion in the sword-like leaves gives the central area of the work a sense of rhythm. The work is asymmetrically balanced through the use of colour: the dominant blue of the right side of the composition is held in balance by a large, lone white iris that draws the eye to the left.

The effect that the formal elements in this work create is one of tension, but a tension that is balanced with serenity. The tension created by the writhing lines of the leaves is matched and neutralized by the serenity of the petals; the intense colour contrasts are subdued to a degree by the cool analogous colours; and the agitated brushstrokes of the tactile soil are neutralized by the soft treatment of the petals. The effect is one of balance in nature. On the one hand, the painting expresses the power and energy that runs through nature; on the other hand it expresses the calm and peaceful state of mind that nature can invoke. The artist himself stated the need for nature in his work and life: "...and nature,...if I didn't have that, I should grow melancholy" (Letters 2: 567). Thus, Van Gogh may have intended to render nature in the Irises in this way: by illustrating the intense spiritual power in nature while simultaneously expressing the calm and tranquil consolation that nature provided him with. His use of formal elements certainly reflects this.

Van Gogh's year in Saint-Rémy was, indeed, very taxing on his faculties. His inner torment during this period has been a well-documented and interpreted phenomenon, and, consequently, Van Gogh's work from this period has been shrouded in a veil of insanity. This is not to say that there is no madness inherent in the artist's works, but rather that there is a certain method that Van Gogh used during the last four years of his life that helped to give his paintings their expressive power. This method is based on the art of Japan, Cloisinisme, and the use of complementary colours. The first element which Van Gogh was to exploit and apply to his painting style were the prints made from Japanese woodblocks. Van Gogh was an avid collector of these prints, fashioned by such artists as Utagawa Hiroshige and Kesai Eisen (Overbeek 57-9). Indeed, Paris in the mid- to late-nineteenth century was fascinated with the Japanese culture. Japanese objects were shown in Paris at the 1867 World Exhibition, and the art of Japan captivated the young impressionists Monet, Renoir, and Degas. These artists admired the prints for their heavy contours and decorative colours, which undermined the academic Salon tradition that they were later to rebel against (Walther 27). The impressionists, however, did not exploit the prints thoroughly, and perhaps the truncated subjects in Degas' work is the closest emulation of the Japanese style among these artists (Welsh-Ovcharov 22). A stronger tendency to the art of Japan was taken by the artists that were working in Paris in the mid-1880s, namely Vincent van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Louis Anquetin, and Emile Bernard. All of these artists were students at the Cormon atelier, and this is where Vincent contacted these artists, which helped to develop his own unique style (Welsh-Ovcharov 26). The art of Japan fully captivated Van Gogh, and he even made copies after some Japanese prints. Vincent used the Japanese style of heavy contours, areas of pure colour, and humble subject matter in his work during the last four years of his life, and the influence of the Japanese prints can be seen directly in the Irises. The work may have been inspired by a print of Utagawa Fusatawe's In an Iris Garden (c. 1860), which Van Gogh owned (Bailey and Collins 10). Moreover, the close up view and sharp sword-like leaves may have been derived from Katsushika Hokusai's Irises and a Grasshopper (c. late 1820s) (Pickvance 81). The areas of pure blue and green, as well as the thick contours that isolate each form, are also based on Japanese prints. The role of Japanese art in Van Gogh's style was a major element in the art that he created during the last four years of his life, and the bold simplicity of this art form contributed greatly to Van Gogh's expressive powers.

The Irises also illustrate another stylistic element that Van Gogh used in his art during the Arles and Saint-Rémy periods: Cloisinisme. It is important to note that although they are very similar, Japanese art and Cloisinisme are different. Both use heavy contours, bounded areas of pure colour, and flat compositions, but they derive from different sources. The french term cloisinné literally means "partition," which refers to its origin, namely in Byzantine enamel work and Medieval stained glass, which use metal partitions and flat areas of pure colour (Welsh-Ovcharov 19). Where as Japanese prints were an imported phenomenon, Cloisinisme was a reaction to the academic style of the Salon artists (Welsh-Ovcharov 20-21). Van Gogh's experience at the Cormon studio was also the source for this element in his later work. Louis Anquetin was credited with "inventing" the style by a Parisian art critic, and Van Gogh was in contact with this artist at the Cormon studio. Like the Japanese influence in the Irises, Van Gogh's "cloisinist" style can be seen in the circumscription of the forms, like the partitions in stained glass; in the areas of solid colour, such as the leaves and the petals; and in the relatively flat composition, like a stained glass window. Van Gogh himself stressed the importance of "cloisinist" techniques in his art: "I want to manage to get colours into [my art] like stained glass windows, and a good, bold design" (Letters 2: 534). As Ingo Walther suggests, the heavy outlines surrounding the forms, such as the petals, were important to Van Gogh because the outlines allowed the artist to isolate objects in a composition and invest them with meaning, thus creating symbols out of objects (Walther 48). The petals and the leaves of the Irises are marked off and do seem to be invested with meaning, which, as I previously mentioned, may be related to the importance of nature to Van Gogh as a means for consolation, and the importance of nature to all life in general.

Another stylistic device that Van Gogh continually employed in his artistic method was colour. As I have already mentioned, the Irises is a virtual exercise in colour theory through its interplay of complementary colours. Van Gogh derived his bright colours from the impressionists in Paris, but his ideas on the expressive possibilities of complementary colours were fostered by the art of Eugene Delacroix: "...what enormous variety of moods did he express in symphonies of colour" (Letters 2: 426). Furthermore, Van Gogh had visited the pointillist painter Georges Seurat prior to leaving for Arles, and most certainly would have been instructed on the juxtaposition of colour areas (Welsh-Ovcharov 158). As I have already suggested, Van Gogh possibly used complementary colours in the Irises to capture the tension and power in nature, but also to capture the fine balance that exists in nature. As Van Gogh himself stated: "colour expresses something in itself, one cannot do without it, one must use it..." (Letters 3: 428). Colour, therefore, played a crucial role in Van Gogh's artistic method because it allowed him to express the true nature of what he painted and what those things meant to him.

The art produced by Van Gogh during the last four years of his life is, without doubt, powerfully expressive. The power of his works to move the viewer may indeed rest on the tragic circumstances of his later life. But the method that Van Gogh employed in his later art is also important. The interrelationships between the art of Japan, the "cloisinist" style, and Van Gogh's use of colour helped to give Van Gogh a method to convey what he felt about nature and his inner torment, and this helps to give his work its powerful and intense expression. One cannot help feeling moved when they view a work by Van Gogh; perhaps this stems from the romantic myth that surrounds his tragic life, or perhaps it is related to the way Van Gogh conveyed his subjects with the stylistic method that I have outlined. Perhaps it is a synthesis of the two. His work nonetheless retains a tremendously expressive quality that is impossible to deny. As one critic, Octave Mirbeau, who owned the Irises, tersely stated: "Oh...how he understood the exquisite soul of flowers" ( qtd. in Welsh-Ovcharov 1974, 67).

Fig. 1: Vincent van Gogh, Irises, (1889).

Fig. 2: Katsushika Hokusai, Irises and a Grasshopper, (c. Late 1820s).

Works Cited

Bailey, Colin B., and John Collins. Van Gogh's Irises: Masterpiece in Focus. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1999.

Minor, Vernon Hyde. Art History's History. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1994.

Overbeek, Annemiek. Van Gogh Museum Guide. Trans. Michael Hoyle. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 1996.

Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986.

Schapiro, Meyer. Vincent van Gogh. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1950.

The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh. 2nd ed. 3 vols. Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society, 1958.

Walther, Ingo F. Vincent van Gogh: Vision and Reality. Trans. Valerie Coyle and Axel Molinski. Hohenzollernring: Benedikt Taschen, 1993.

Welsh-Ovcharov, Bogomila, ed. Van Gogh in Perspective. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1974.

Welsh-Ovcharov, Bogomila. Vincent van Gogh and the Birth of Cloisinism. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1981.

Return to Visitor Submissions page

Return to Visitor Submissions page

Return to main Van Gogh Gallery page

Return to main Van Gogh Gallery page